stately homes that have been built on the slave trate photos - Bing images

Cannot blame anyone family for the Slave Traders it was all over the world.

Walking Bristol’s slave trade - Geographical Magazine

Modern Day Slavery - Study Hall (weebly.com)

It still happens today

UK slavery network 'had 400 victims' - BBC News

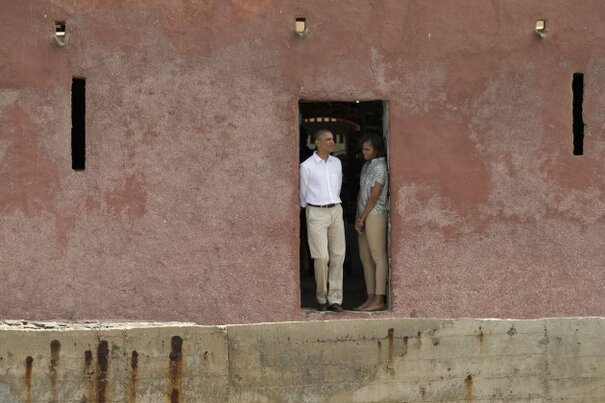

The Day Prince Albert apologized for slaveryPosted bydudleyiimcMarch 24, 2022Posted inUncategorized

“Never make a defense or an apology until you are accused“

– King Charles I

How often should descendants apologize for an act that their great grandparents already made an apology for? In the context of presendence and the royal prerogative, it is not correct to repeat that which was already done by a former head of the monarchy.

In June 1840, Prince Albert addressed a large International Anti-Slavery meeting called the Society for the extinction of the Slave Trade, & for the Civilization of Africa, at the Exeter Hall in London, in which he stated his wife’s (Queen Victoria’s) whole-hearted support for the efforts of Thomas Fowell-Buxton (successor of William Wilberforce) and the British anti-slavery lobby. It was the first time the monarchy ever associated themselves with a political cause.

A section of Prince Albert’s hand written speech reads,

“I have been induced to preside at the meeting of this Society, from a conviction of paramount importance to the great interest of humanity and justice.

I deeply regret the benevolent and persevering exertions of England, to abolish that atrocious traffic in human beings (at once the desolation of Africa and the blackest stain upon civilized Europe). But I sincerely trust that this great country will not relax in its efforts, until it has finally and forever put an end to a state of things, so repugnant to the spirit of Christianity and the best feelings of our nature….”

This apology for slavery engendered adoration for Queen Victoria and one of the reasons why her statue was errected in what we now call St William Grant Park. In the Cathedral Church of St Jago de la Vega, looking down from the walls of the chancel among twelve corbels are two Negro heads along with that of Queen Victoria in tribute to the Victorian empire, and immortalizing the significance of their contributions in ending slavery.

PS: Regret and be sorry are both used to say that someone feels sadness or disappointment about something that has happened, or about something they have done. Regret is more formal than be sorry. Regret is only used in formal letters and announcements. Was Prince Albert’s address a formal one?

Also published in Jamaica Observer Friday March 25, 2022 as How many apologies are required? https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/letters/how-many-apologies-are-required-_247069

Prince Albert | The Royal Family

The Five Punishments for Chinese Slaves BY GAVIN ALEXANDER • JULY 21, 2018

Five Punishments: A Chinese man with hands tied and forced to kneel in public. Circa 1900. (Hawley C. White / Library of Congress)

The journey of mankind has been filled with joy, discovery and wonder. Unfortunately, it has done so alongside pain, evil and shame. To begin the Chinese theme, this connection of opposing sides is symbolic to the famous Chinese philosophy of Yin and Yang, illustrating that conflicting factors are complementary, even dependant on one another. Perhaps the same can be said for crime and punishment, that they are a necessary entity of everyday life.

In much of the world today, forms of torture are frowned upon and even for criminals, alternative forms are encouraged in most countries. It is an attitude that feels right; to save a population from desensitising and returning to a barbaric system of justice. It also inhibits the famous eye for an eye principle which uses a take from me and I take from you legal philosophy.

Anything from money, land or ultimately, an eye. This idiom was first mentioned in the Book of Hammurabi from ancient Mesopotamia – a functioning civilisation which harboured torturous punishments also. Much of the world has changed so much since that time making it hard to imagine that torture was once a mainstay. Commonly practised and an accepted form of punishment in every corner of the world, even within governments. One such place was and is the great land of China.

Punishments for slaves in Old ChinaThis is best proved by the fact that the death sentence is still passed in China today, illustrating that corporal punishment is not designated to the past, and perhaps has a place in the future. There are also the numerous reports that torture techniques are still in practice, for example in secret prisons. China is one of the cradles of civilisation, as one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world.

The first written history comes from a period known as Dynastic China when the Xia Dynasty ruled from 2070 BCE. It is in the centuries before this period when a series of horrifying penalties known as The Five Punishments were written to keep slaves under control and maintain social order. Slavery was a massive cog in the Chinese economic system during this time.

People were born, sold or captured into slavery and their main duties – within a tough life – would be farming. Some slaves would also work with the dynastic families themselves. Around the centuries before the inception of the Xia, these punishments were created although their exact origins are unknown. They seem to have originated from an indigenous people known as the Hmong (Miao) however, a group from the south of China.

The reason for this is that a famed warrior known as Chiyou is heavily involved. His specific clan was unknown but many link it to the Hmong or their allies. For instance, the Sanmiao or the Nine Li. He is regarded as a mythical king and a great warrior. The Xia dynasty adopted these punishments and made them known to their people. They were for men only as women had their own separate punishments which will be listed later.

Five Punishments in Dynastic ChinaFace tattooed with permanent ink.Nose cut off without anaestheticRemoval of foot/feet or kneecap without anaestheticRemoval of reproductive organs without anaestheticDeath in various forms (including quartering (cutting the body into four pieces), decapitation, drawn out by chariots, strangulation/asphyxiation, slicing by thousands of small cuts.)In 221 BCE, a ruler called Qin Shi Huang brought about a time known as the Imperial Era. He conquered the dynastic states and made himself Emperor of the collective land known as Qin, later to be called China. During this imperial era his reforms made the punishments less barbaric but none the less still torturous. The improvement of standards is attributed to the teachings of famous philosopher Confucius and his views on human life. The Imperial penalties were as follows,

Bamboo lashes to the buttocks (the number of lashes depended on the nature of the crime)Stick lashes to the back, buttocks or legsPenal service (ranging from 1-3 years)Exile – (this would be to a remote location such as the island of Hainan to the south, the distance depended on the crime)Death (strangulation, slicing or decapitation)

A lawbreaker being whipped while two men restraint him. (Ralph Repo / Flickr)

It must be said that slaves could also pay their way out of these brutal punishments but the prices were extortionate meaning that very few could do so.

For females the punishments were different. There are no concrete reasons why at this point it is simply thought that because China was a patriarchal society in which woman were not held responsible for their crimes. And that they could not suffer as much as male serfs. As follows,

Forced to grind grainFingers squeezed between sticksBeaten with wooden sticksForced suicideSolitary confinement (time dependant on crime) or Sequestration (losing assets).As mentioned, although torture was inherently part of life in all corners of the world, in Chinese culture it seems incredibly more brutal, especially to be so intertwined with government and society, somewhat uniquely. Perhaps the extreme scale of the land and the amount of warring factions gave a higher rise for the need to control. China is such a different world – as are many – for outsiders to comprehend.

There are many works which try to associate the mindset, for example to why their laws arose and why many still continue. Skipping over the nature which brought about torture in the first place (as that would require a tome to even attempt to fathom why) we will look instead at the change from Dynastic to Imperial. When punishments looked to improve after people started becoming enlightened.

This possibly began when the teacher and philosopher Confucius resided and taught. Born in 551 BC his teachings spread more after his life ended and influenced many of his countrymen. The work Crime and Punishment in Ancient China and its Relevance Today explains more,

“Confucianism was designed to maintain civility in the absence of central authority by persuading leaders to create a harmonious society based on the limited use of raw power and punishment.”

Helping Confucianism was the cosmological tradition which was established after his death, around 330 BC during the Warring States Era. This was where many dynasties vied with each other to create an Empire. Like the five punishments, this tradition is based on the five major planets and the elements they represent: Venus (metal), Jupiter (wood), Mercury (water), Mars (fire) and Saturn (Earth). The people used this to monitor agriculture, climate, politics and warfare. In 170 BC a document was found relating these five entities to each other. It is called the Five Star Oracle. Confucianism, as well as the cosmological tradition helped people in this aspect by introducing more moralistic behaviour and by trying to attain a balance among nature. Punishments were not just required for social order but to balance complex natural phenomena. Deborah Cao explains more,

“The cosmologists believed that without an appropriate effort to remedy the social harm caused by a crime, the disturbance of the human order would affect the larger cosmic order of things. Through negative natural phenomena, such as… floods, disturbances of the cosmos would in terms have a negative impact on the human world.”

Although this period certainly lessened torture techniques, the death penalty continued was implemented and advocated by Shang Yang (390 BCE). He founded Chinese Legalism which promoted a strict system. Crime and Punishment in Ancient China and its Relevance Today again explains more.

“The Legalist tradition restored harsh punishment as a way to impose order upon a fragmented society in which local despots had been carrying out arbitrary judgments. But Legalism carried the seeds of its own destruction and required Confucianism to balance it in creating a durable system of governance and justice.”

It looks as though each system – Confucianism and Legalism – worked alongside each other, again like an interconnected Yin and Yang. This was perhaps one of the first documented times that legality and severe punishment went hand-in-hand with socialism. With it, more thought was put into social problems.

Cangue PunishmentPunishment of course continued in other forms. Here is an example of a torture used even until the 20th century, a technique called a Cangue board used in many parts of Asia. It was implemented in other parts of the world also such as England where it was known as a Pillory. The Pillory device, however, would be fixed to the ground while the Cangue could be moved by the recipient if needed. It obviously restricted movements even to the point where people could not feed themselves, resulting in starvation in many cases unless they had friends and family to help them, otherwise strangers. The prisoner would be in the Cangue for as long as the punishment merited, it was mostly the sentence for thieves.

A man being punished by cangue. (John Thomson / Wellcome Images)

These methods continued until China became a Republic in 1912. Then it became westernised and more socialism brought about changes in punishment techniques, making them less brutal. Although as shown with the death penalty, the older traditions remain in China, whereas in other countries the death penalty has been outlawed completely. China, according to Amnesty International accounts for the majority of capital punishments on Earth.

Like many countries, China developed a culture of punishment and torture. However, unlink many countries such as in Western Europe they have kept aspects of it such as the death penalty. There are also many reports regarding punishments similar to the Five going on in secret prisons known as ‘Black Prisons’. The famous bamboo shoot and water torture are a few of the methods practiced.

European installations like the Council of Europe make banning capital punishment a mainstay if a country wishes to join. This is to do with the miscarriage of justice which can occur. More is explained in a deep study by the Economist. It is not just a sentimental gesture, however. Another reason is for keeping political contests fair, as many reports of killing political opponents this way have been reported none more so in China.

“For many emerging democracies, abolishing the death penalty has also been a way to make a decisive break with an authoritarian past, when governments used capital punishment not just to punish criminals but to get rid of political opponents, as China currently seems to be doing in Xinjiang against the province’s Muslims.”

This will long be a contentious element between nations on whether the death penalty is just. For the reasons above it seems a valid argument to abolish it yet oppositely, for serial killers and crowded prisons it becomes more apt. But just where can the line be drawn or known between the two.

Rebels undergoing a slow painful death inside a cage. (Jeff Lea / Wikimedia Commons)

A clearer point can be with torture. It seems simpler in that there is now a consensus flowing through the world that any form of torture is wrong, whatever the crime. It still goes on, that goes without saying but soon hopefully it will be completely resigned to the past. Even reading about these torture techniques is absolutely harrowing, to think of what some people went through, some no doubt innocent. May they rest in peace and be eternally remembered so that the practice of torture is ceased, once and for all.

Enjoyed this article? Also, check out “The Head Crusher – A Renaissance Torture Device for Slow and Incrementally Agonising Punishment“.

Photos Of Slavery From The Past That Will Horrify You - YouTube

Asia has had a slave trade as well as the Middle East for many years, not sure if it has even finished.

In Pictures: Islam's Sexual Enslavement of White Women - American Renaissance (amren.com)

And yes white people have been slaves also.

White Slavery

White Slavery | Jewish Women's Archive (jwa.org)

by Nelly Las

Last updated June 23, 2021

Official Report from the JAPGW International Conference, June 22-24, 1927.In Brief

Official Report from the JAPGW International Conference, June 22-24, 1927.In Brief“White slavery traffic” was an expansion of the prostitution that spread throughout the world in the first years of the twentieth century, following the massive emigration to the New World and resulting from the growing poverty and misery of European women in the age of industrialization. Those who initiated the struggle against white slavery in Europe and America were mainly women. Among them were leading Jewish women's organizations (from the United States, England, and Germany); they established committees against “white slavery” in several countries, sending representatives to the international conferences combating trafficking in women and girls: in Paris in 1902, Madrid in 1910, and London in 1913. All these struggles have led to significant anti-trafficking legislation during that time.

Contents1 Introduction2 Jewish Prostitution and Trafficking in Women3 Jewish Sex Traffickers4 Jewish Women Against Sex Trafficking5 Conclusion6 BibliographyIntroduction“White slavery traffic” was in part an extension of the prostitution that spread throughout the world in the nineteenth century, following the beginnings of massive emigration to the New World. It was also a result of the growing poverty of European women in the age of industrialization that continued in the next century. Large European cities such as Paris and London housed thousands of prostitutes and governments did nothing to contain the problem, contenting themselves with preserving public order and ordering medical inspections to reduce the risk of venereal disease. The women had to undergo medical examinations and register as prostitutes, while the men who were consumers of their sexual services were not required to undergo any examinations and were immune to legal prosecution.

The enormous spread of prostitution in Europe, and specifically its transformation into an international trade over the second half of the nineteenth century, can be attributed to several factors, including:

The great distress of women who entered the workforce en masse, under terrible conditions, during the Industrial Revolution;The migration from villages to cities, which caused both difficulties in adapting and a loss of direction, especially for vulnerable women who had no status;The migration of men from Europe to the New World, which created large concentrations of men and led to the increased demand for prostitutes in those locations;The delayed marriage of bourgeois men until they had sufficient resources to support a family. Because gender norms of bourgeois society did not permit sexual relations outside marriage with women of their own class, single young bourgeois males turned to prostitutes.The public panicked when newspapers reported kidnappings of women and wrote of young girls who were forced into prostitution under false pretenses and taken to brothels in distant countries. Committees and international meetings were held in various places in the world to place the subject on the public agenda and seek ways of combating the phenomenon. This form of prostitution, called at the time “white slavery,” was considered different from voluntary prostitution, given its severity and cruelty.

See Also: Encyclopedia: Juedischer Frauenbund (The League of Jewish Women)

Encyclopedia: Juedischer Frauenbund (The League of Jewish Women)The silence was broken for the first time in England by Josephine Butler (1828–1906), the daughter of an Anglican abolitionist minister, who beginning in 1864 led a campaign against the regulation of prostitution, which she deemed immoral. Believing that the government should concern itself with the social and economic causes of prostitution, Butler founded the Ladies National Association (LNA) and the International Abolitionist Federation to fight prostitution in 1875. In the late nineteenth century, when international traffic in prostitutes was organized, using corrupt means and often working clandestinely, Josephine Butler’s organization set up national committees to work against white slavery in the capitals of Europe, Egypt, Canada, the United States, South America, and South Africa.

In England, the campaigns against “white slavery” culminated in a rally in Hyde Park, London, in August 1885, when tens of thousands of people demanded that white slavery be outlawed and the age of consent for girls be raised. The first measure to be adopted was the Criminal Law Amendment Act (CLAA) of 1885, which gave a definition of a trafficked girl: an involuntary prostitute.

In the United States, the term “white slavery” had been used since the seventeenth century to refer to a wide range of exploitative labor practices. By 1907, it emerged as a serious mainstream human rights issue against sex trafficking, described by the press as a form of hysteria. In fact, the period between 1907 and 1914 corresponded to a period of widespread immigration to the United States that generated considerable fear and anxiety, especially in response to stories about sex traffickers using marriage as a method to entrap their victims, as well as other methods

Jewish Prostitution and Trafficking in WomenJewish trafficking in women did not begin in a vacuum. Jews joined the crime wave that swept East European Jewish society and spread throughout the world. Prostitution and international trafficking in women, among the gravest plagues in Western society from the end of the nineteenth century on, did not bypass Jewish society, which had been undergoing enormous changes since the 1880s. The migration from town to city and the increase in poverty contributed to the development of prostitution among Jews. Most big cities that contained large, poor populations of Jews (Warsaw, Odessa, Vilna, Cracow, Budapest, and Vienna, for example) saw concentrations of Jewish prostitutes working in brothels for Jewish pimps. It was virtually impossible to work as a prostitute in small towns and shtetls where everyone knew everybody else and prostitutes were ostracized. In large cities, prostitution took place in certain sections known to be controlled by the Jewish underworld, to which the authorities turned a blind eye. Between 1872 and 1890 Jewish women constituted seventeen to twenty-three percent of all Warsaw’s registered prostitutes, who in 1890 numbered 962. At the time, the Jewish population (c. 300,000) constituted one-third of the city’s total population (Bristow 55). In 1908, the American consul in Odessa reported that “All the business of prostitution in the city is in the hands of the Jews” (Bristow 56). In Minsk in 1910, 226 women were registered as prostitutes, 67 of whom were Jews. On the other hand, it was reported that half the prostitutes hospitalized for venereal disease in the city were Jews (Bristow 64).

In addition to the general causes of prostitution, such as economic distress, loss of parental authority, and the weakening of the family as a result of poverty, two additional factors were specific to Jews: antisemitic persecution and the restrictions placed on Jews. These caused overcrowding, poverty, and unemployment, creating a fertile environment for crime among unemployed men, while a number of young Jewish women found refuge from economic distress by working as prostitutes. In Russia, where Jews were generally permitted to live only in restricted areas (the Pale of Settlement), a Jewish woman registered as a prostitute could receive a permit to remain in a city such as St. Petersburg. Paradoxically, it was this badge of shame that allowed poor Jewish women an existence beyond hunger and poverty. Some of the registered Jewish prostitutes were not destitute, rather seeking permits to live in St. Petersburg or Moscow in order to acquire higher education.

See Also: Encyclopedia: Hannah Karminski

Encyclopedia: Hannah KarminskiHowever, the increase in prostitution among Jews stemmed mainly from the large waves of migration that occurred among Jews in Eastern Europe, beginning in 1880. Over approximately sixty years, millions of Jews endured wandering, hardship, separation of families, loss of direction, and a break in tradition.

Jewish Sex TraffickersSince unscrupulous Jews active in the underworld were familiar with the customs and traditions of Jewish society, they knew how to exploit the innocence of young Jewish girls. The inferior status of Jewish women combined with Jewish religious law to render them especially vulnerable and contributed to their falling into the hands of sex traffickers. Sex trafficking, which developed in the surrounding society, drew Jewish criminals into profitable sex deals. Several contented themselves with local deals, while others exported prostitution to distant lands. While many young women were brought into prostitution unwittingly, some worked as prostitutes in their home towns and hoped to improve their fortunes in richer countries. Most of these willing prostitutes were also victim to the false promises of their pimps, finding themselves in an inferior position in a foreign country, not knowing the language and completely dependent on their pimps because of the debts they had accumulated.

To entice their victims, Jewish sex traffickers used newspaper advertisements for jobs, the promise of an immigration certificate, and marriage proposals, all the while taking advantage of the parents’ naiveté and poverty. They knew, for example, that a Jewish wedding requires two witnesses and a ring and that a rabbi is not necessary. The “secret wedding ceremony” became one of the methods for bringing Jewish women into prostitution. One trafficker managed to marry a record twelve women and send them into prostitution (Bristow 104).

The second evil was the problem of agunot (anchored wives). Women whose husbands died without witnesses or went missing without leaving a writ of divorce became agunot—with no status, helpless and vulnerable to trafficking. Many husbands who went on journeys without their wives in order to try their luck in America “forgot” to send their wives any sign of life. Others never returned from war, but their deaths could not be proven.

Before World War I, the National Desertion Bureau was established in New York to search for delinquent husbands. In 1929 the World Jewish Women’s Congress in Hamburg, Germany, reporting on 25,000 agunot in greater Poland alone, described the situation as the catastrophe of Eastern European Jews (JTA Bulletin, June 26, 1929).

See Also: Encyclopedia: Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women

Encyclopedia: Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and WomenJewish sex traffickers were prominent in major transit points from Europe to Latin America, such as Berlin, London, and Hamburg. In the latter, for example, of 402 sex traffickers caught by police in 1912, 271 were Jewish (Bristow 52–53). Although the facts speak for themselves, there was also a tendency to exaggerate the percentage of Jewish sex traffickers and Jewish prostitutes because it was easier to condemn an entire group, especially if they were Jews. At a time when antisemitism was increasing throughout the world, reports of the involvement of so many Jews in such shady dealings caused a great deal of damage to the image of Jews and were used by antisemites. Jewish communities found it difficult to deal with this embarrassing problem and for a long time ignored it, until newspaper reports forced them to confront it.

The problem of prostitution among Jews began in Eastern European countries and spread throughout most of the world in which trafficking in women existed. The Jewish prostitution networks recruited young women in Eastern Europe and brought them via transit stations across Europe to various destinations throughout the world. Preferred destinations were South America (Buenos Aires , São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro), the United States (New York, Chicago, Philadelphia), South Africa, Turkey (Constantinople), and Egypt. In addition to their moral outrage over the phenomenon itself, the local Jewish communities suffered greatly from the stigma that resulted from Jewish involvement in prostitution. The chief method they used to fight traffickers and prostitutes was ostracism. The “impure ones,” as they were termed, were not permitted entry into the community’s synagogues or burial in its cemeteries. In Buenos Aires, traffickers in women formed their own society, Zwi Migdal, which established its own synagogues and cemeteries.

Beginning in 1910, after years of apathy and denial, most important Jewish organizations established committees against “white slavery,” sending representatives to international conferences on the topic. The severity of the situation and the official statistics of Jews involved in criminal activity made it impossible to continue to ignore the issue. Yet before the Jewish organizations were forced to intervene, well-to-do Jewish women did a great deal to convince Jewish community leaders of the severity of the problem. They prepared the ground, organizing an infrastructure of wide-scale activity to protect immigrant Jewish women and young girls from the dangers that lay in wait for them.

Jewish Women Against Sex Trafficking Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea Alexander Bassano, circa 1898

Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea Alexander Bassano, circa 1898During the nineteenth century, women developed a wide network of charitable and social work. According to a census in Great Britain in 1891, over 500,000 women were involved in philanthropic work (Hubbard 361–366). At the same time, a change developed in the attitude toward the poor. In the past, charity had been considered a religious duty and poverty connected with moral decline. Now, a more complex analysis of the reasons for poverty and a new kind of social involvement came into being. Monetary donations were no longer enough; personal involvement was necessary. This involved home visits, visits to prisoners, prisoner rehabilitation, adult education, and so on. Beginning with the waves of immigration of 1881, the women activists turned their attention to social work on behalf of immigrant girls and the subject of white slavery. Christian women’s organizations were founded to protect young immigrant women. Some of these had names such as the International Catholic Girls’ Protection Society and the Travelers’ Aid Society.

Well-to-do Jewish women could not join the Christian charitable organizations of the surrounding society, nor could they participate in the leadership of Jewish organizations, which were headed by men. Therefore, like their Christian neighbors, they decided to form their own organizations to help their needy co-religionists. Established at the end of the nineteenth century, these organizations became stronger during the twentieth century, contributing to the entry of women into public life and their participation in various significant social struggles

German suffragette Bertha Pappenheim in her riding outfit.

German suffragette Bertha Pappenheim in her riding outfit.Institution: Noemi Staszewski

Jewish women involved in public activity encountered the subject of white slavery for the first time in international committees of women’s organizations and in committees on trafficking in women. They were horrified to hear statistics about Jewish involvement in crime and about the unprecedented number of Jewish women involved in prostitution. Several leaders who headed the public and social struggle on behalf of women in distress in Europe and in immigration destinations such as the United States were among the first to deal with the problem in a practical way. These pioneers included Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea, of Great Britain, Bertha Pappenheim of Germany, and Sadie American of the United States. They influenced Jewish women in other countries to join the struggle against trafficking in women in the Jewish world, though at first they encountered opposition from community leaders, mainly Orthodox men and rabbis who were repelled by the subject.

Great Britain

Though the struggle against the institution of white slavery existed in Great Britain from the beginning of the nineteenth century, for a long time the Jewish community ignored the concentration of Jewish prostitutes in the immigrant district of London. In 1885, when Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea, the daughter of Anthony de Rothschild (1810–1876), first learned about the grave situation of immigrant Jewish women in her city, she decided to act, first establishing a shelter for Jewish women in distress. Through this shelter, women received immediate aid, instruction in English, and professional training. In the same year Lady Battersea Rothschild established the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women (JAPGW). To give more status to the new organization, she recruited to its leadership such well-known Jewish community leaders as Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore (1858–1938) and Artur Moro, who were also her relatives. In 1889, when London became a transit point for masses of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, and as a result a center for traffickers in women, Constance Rothschild Battersea decided that the situation was severe enough to warrant the supervision of the leaders of Jewish communal institutions. The women continued to take the rescue and aid work upon themselves.

See Also: Encyclopedia: National Council of Jewish Women

Encyclopedia: National Council of Jewish WomenThe JAPGW was later supported by the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), though the JCA hesitated a great deal before agreeing to become involved in the fight against sex trafficking in the Jewish world. Like other Jewish organizations, it feared to associate itself so closely with a topic so loaded with negative connotations that could harm its image. Later it developed a wide-scale apparatus for preventing crime and assisting organizations that aided young women in distress.

France

From 1910 on, many other Jewish organizations became involved in combating white slavery. For example, the French Association israélite de protection de la jeune fille (Jewish Association for the Protection of Young Girls) was founded in 1910 by a group of Jewish ladies. Confronted with the sensitive subject of white slavery, the French Jewish community had long hesitated to deal with it officially, motivated by fear of antisemitism following the Dreyfus Affair. The new organization was supported first by the Jewish Colonization Association and the JAPGW, but not yet by an official body of the French Jewry. Its first president was the prestigious baroness Adélaïde de Rothschild, wife of the famous philanthropist Edmond de Rothschild, but it seems that the focus of the Association israélite was more on helping isolated girls in difficulty, Jewish and non-Jewish, through social assistance, moralizing, and educating, rather than fighting trafficking on women.

Germany

Unlike Great Britain, where women passed the struggle to men, contenting themselves with the practical work of aid and rescue, Jewish feminists in Germany placed themselves at the center of the fight against sex trafficking.

See Also: Encyclopedia: Central Organizations of Jews in Germany (1933-1943)

Encyclopedia: Central Organizations of Jews in Germany (1933-1943)The major initiator was Bertha Pappenheim, who came from a well-to-do Orthodox family in Germany and was active in Jewish feminist organizations. She first learned of Jewish involvement in prostitution in 1902 at an international meeting on sex slavery. From then on she participated fully in the struggle against this plague, which she felt had its origins in poverty, ignorance, and the inferior status of Jewish women as expressed mostly in the laws of marriage and divorce. She was repelled by the stigma of the “old maid,” which was considered a family disaster among Jews, and by the tendency of Jewish families to shun daughters who had strayed from the path, committing even one transgression. She believed this led many women to despair and thus to fall prey to sex traffickers.

Pappenheim visited many places where white slavery was flourishing, including Galicia, Russia, Hungary, Bulgaria, the Balkans, Palestine, and Egypt, to study the subject close up and to raise the attention of Jewish communities to the necessity of keeping young Jewish girls from degradation. She wrote her impressions in letters sent from the places she visited (1911–1912), published in a book entitled Sisyphus-Arbeit (1911), where she related how she tried desperately to inform Jewish communities of the gravity of the situation. She asserted that the silence of Jewish community leaders, who claimed they feared antisemitism to justify their non-intervention, was actually a kind of collaboration with the crime. The Jüdischer Frauenbund, which she established in 1904, unified most of the Jewish women’s organizations in Germany. Within several years it became one of the largest Jewish women’s organizations in the world, numbering 50,000 members in 1920. It worked a great deal against trafficking in women, mostly through prevention. It supported the establishment of girls’ schools in Poland, sent letters to Jewish families, circulated flyers warning them against job offers in newspapers and arranged marriages abroad, established aid stations in ports and railway stations in European cities, where volunteers wearing the Magen David symbol guided unaccompanied girls, and established clubs and shelters for women in distress. For close to twenty-seven years Bertha Pappenheim ran a shelter, one of the largest in Europe, in Neu-Isenburg, near Frankfurt, for single mothers in distress and their children.

The United States

Cecilia Razovsky (center) spent her life striving to assist immigrants in adapting to life in the United States and other countries. She was an influential member of many organizations, including the National Council of Jewish Women. Her writing on and study of immigration issues helped to define elements of United States policy.Institution: American Jewish Historical Society

Cecilia Razovsky (center) spent her life striving to assist immigrants in adapting to life in the United States and other countries. She was an influential member of many organizations, including the National Council of Jewish Women. Her writing on and study of immigration issues helped to define elements of United States policy.Institution: American Jewish Historical SocietyThe periodic international conferences to which representatives of Jewish women’s organizations were invited provided an opportunity for them to exchange opinions and information regarding the vital issues of the various Jewish communities. At one such conference, the American delegates were convinced that they must take an active part in helping Jewish women immigrating to the United States, who were helpless and vulnerable to white slavers.

Criminal activity of all sorts developed in New York City, where tens of thousands of Jewish immigrants lived. There are accounts of Jewish prostitutes who were found and arrested in New York. As in Buenos Aires, the New York community dealt with the struggle by shunning the “impure ones.” While this tactic perhaps saved the community’s reputation, it did nothing to solve the human problems that led so many Jewish women into prostitution.

President of the National Council of Jewish Women from 1920 to 1926, Rose Brenner (1884-1926) provided strong leadership, almost doubling the size of the organization. The NCJW has always championed both public service and the role of traditional motherhood; indeed, Brenner is the only unmarried woman ever to be president. Institution: The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and Bachrach.

President of the National Council of Jewish Women from 1920 to 1926, Rose Brenner (1884-1926) provided strong leadership, almost doubling the size of the organization. The NCJW has always championed both public service and the role of traditional motherhood; indeed, Brenner is the only unmarried woman ever to be president. Institution: The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and Bachrach.The National Council of Jewish Women in America (NCJW) led by women such as Sadie American, Rose Brenner, and Cecilia Razovsky, developed wide-scale rescue activity for immigrant Jewish women. Volunteers who received lists of young immigrant women made sure to meet them at the port and bring them to one of the guest houses that had been established in various cities, where they received professional training and the help they needed to settle in their new country. Between 1908 and 1911 the organization helped 19,377 young girls, 4,020 women, and 6,427 children (Baum et al. 51). Thanks to this wide-scale activity, the NCJW won prestige and great appreciation from women’s groups in America and Europe and received governmental recognition for its work at the port of New York. In 1910, at the international conference against white slavery in Spain, Sadie American was welcomed by the king and queen of Spain, who praised her for her organization’s work (Baum et al. 166).

See Also: Encyclopedia: Bertha Pappenheim

Encyclopedia: Bertha PappenheimThe cooperation of women’s organizations in Great Britain, Germany, and the United States regarding sex trafficking prepared them to strengthen their contacts and unite their forces and contributed to the establishment of international Jewish women’s organizations throughout the world (Las 1996). Jewish women’s organizations were active in Cracow, Riga, Latvia, Hungary, Warsaw, and most places where women were at risk. Each organization worked according to its ability and initiative. Some offered courses in literacy and sewing and professional training for women or opened women’s employment bureaus. They sent volunteers to transit stations to help needy women and published warnings against white slavers, and some even volunteered to search for absent husbands.

Two impressive international conferences of Jewish women took place in the 1920s, one in Vienna in 1923 and the other in Hamburg in 1929. They discussed all the problems and difficulties of the Jewish people at the time, including the distress of Jewish women, white slavery, and the problem of agunot (JCB News Bulletin, London, May 1923). The needs of the time and the amount of distress among Jews required international coordination and cooperation, but the women’s organizations did not have the means that the well-established, powerful Jewish organizations possessed. Nevertheless, through daring and determination they succeeded in building an infrastructure of mutual aid, rescuing thousands of Jewish women from moral degradation and suffering.

Apart from these impressive international Jewish women's meetings, the leading Jewish women's organizations (from the United States, England, and Germany) were involved in the general struggle against international trafficking and participated in all the international conferences combating trafficking in women and girls: in Paris in 1902, Madrid in 1910, and London in 1913.

These civil society international conferences were followed by official governmental international cooperation in the fight against sex trafficking. After World War I, the agreements would come under the umbrella of the League of Nations, which became the preeminent site of anti-sex trafficking activism during the interwar period. The first half of the twentieth century saw a number of international conventions regarding white slave traffic:

International Agreement for the Suppression of the “White Slave Traffic,” Paris, 1904International Convention for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic, Paris, 1910International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children, Geneva, 1921International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women of Full Age, Geneva, 1933Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others, Lake Success, NY, 1950(Note: The 1921 Conference of the International Bureau for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons dropped the term "white slavery" for the less loaded term "traffic in women and children.")

ConclusionThe difficulty in coping with so grave a phenomenon did not prevent innumerable activists from devoting themselves to fighting it with all the energy they possessed. Those who initiated the struggle against white slavery in Europe and America were women. For Jewish women, this was their first attempt to cope publicly with a social issue that had such broad implications. They were the ones who succeeded in overcoming the shame and discomfort inherent in the subject of prostitution; they were the ones who initiated effective rescue and prevention work. Thanks to them, thousands of young Jewish women were saved from prostitution. We must remember that during this period women had no political rights in most countries in the world, and their ability to influence was confined to volunteer work and women’s organizations. At a time when Jewish community leaders hesitated to get involved and were afraid to mention the problem of prostitution, women took part in international conferences against the enslaving of women, where they had to confront embarrassing statistics regarding Jewish involvement in sex trafficking. They proved their ability to deal with this severe ethical and human problem despite the restrictions under which they had to function.

BibliographyBartley, Paula. Prostitution: Prevention and Reform in England, 1860–1914. London: Routledge, 2000.

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel. Jewish Women in America. New York: The Dial Press, 1976.

Bristow, Edward J. Prostitution and Prejudice: The Jewish Fight against White Slavery, 1879–1939. Oxford: Schocken, 1982.

Butler, Josephine E. Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade (Westport, Connecticut: Hyperion Press, 1911)

Cordasco, Francesco. The White Slave Trade and the Immigrants. Detroit: Blaine/Ethridge Books, 1981.

Gartner, Lloyd P. “Anglo-Jewry and the Jewish International Traffic in Prostitution, 1885–1914.” AJS Review 7–8 (1983): pp. 129–78.

Goren, Arthur. New York Jews and the Quest of Community. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Hubbard, Louis. Statistics of Women’s Work. London: 1893.

JCB News Bulletin, London: May 1923.

JTA Bulletin, June 1929.

Kaplan, Marion. The Jewish Feminist Movement in Germany: The Campaigns of the Jüdischer Frauenbund, 1904–1938. London: Praeger, 1979.

Knepper, Paul. “’Jewish Trafficking’ and London Jews in the Age of Migration.” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 6 (2007): 239–56.

Kuzmack, Linda Gordon. Woman’s Cause: The Jewish Woman’s Movement in England and the United States: 1881–1993. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1990.

Las, Nelly. Jewish Women in a Changing World: A History of the International Council of Jewish Women (1899–1995). Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1996.

Las, Nelly. “Prostitution and White Slave Traffic in Jewish Society at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century” (Hebrew). Kivunim Hadashim 5 (October 2001).

Pappenheim, Bertha. Sisyphus-Arbeit, Leipzig: P.E. Linder, 1924 (French translation: Le Travail de Sisyphe. Paris: Des Femmes, 1986).

Report of the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women, for the year ending December 31, 1927 in: League of Nations, Geneva, February 8, 1928.

Rogow, Faith. Gone to Another Meeting: The National Council of Jewish Women, 1893–1993. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Vaupen Joseph. The Nafkeh and the Lady: Jews, Prostitutes and Progressives in New York City, 1900-1930. Phd diss., New York University, 1986.

More Like This

Melbourne couple who kept a grandmother as slave for eight years jailed for 'crime against humanity'By court reporter Danny Tran

Posted Wed 21 Jul 2021 at 12:45pmWednesday 21 Jul 2021 at 12:45pm, updated Wed 21 Jul 2021 at 9:06pmWednesday 21 Jul 2021 at 9:06pm

The court condemned Khandasamy (left) and Kumuthini Kannan (right) for their crimes.(AAP: James Ross)Share this articleabc.net.au/news/melbourne-couple-who-kept-slave-sentenced/100310094COPY LINKSHARE

A Melbourne couple found guilty of secretly enslaving a woman in their suburban home for close to a decade have been jailed for their "crime against humanity".

Key points:Kandasamy and Kumuthini Kannan were found guilty of using the woman as a slave from 2007 to 2015The woman endured physical abuse at the hands of her captors, suffering permanent injuriesThe legal team for the couple has not ruled out appealing the sentence

Kandasamy and Kumuthini Kannan on Wednesday appeared in Victoria's Supreme Court where they were convicted for subjugating the woman, which ultimately left her in hospital weighing just 40 kilograms.

Kumuthini Kannan, 53, was ordered to spend eight years behind bars.

Her husband, Kandasamy Kannan, 57, was ordered to serve six years.

It is the first time a case solely about slavery by domestic servitude has been aired in an Australian court and, prosecutors say, the longest period of enslavement the nation has ever seen.

But the court heard the couple still did not accept that they forced the Indian grandmother into servitude, and continued to "strenuously" profess their innocence.

The couple's legal team has already indicated that they may be preparing an appeal.

During a sentencing which was watched by almost 200 people, and which stretched to almost three hours, Justice John Champion took aim at the couple.

"Slavery is regarded as a crime against humanity," he said.

"Your offending occurred in the daily presence and with the obvious knowledge and comprehension of your children.

"You set them a deplorable example of how parents should act towards another human being.

"Her life was controlled largely in the privacy of your own home and care was taken by you to keep her true status from others in your community … so that your dirty secret was maintained.

"This court publicly condemns you both for your disgraceful conduct."

Justice Champion branded the couple as "almost compulsive liars".

"The number and brazen quality of the lies has been nothing short of astonishing," he said.

"I'm quite convinced that you both believe you have done nothing wrong.

"Neither of you have shown remorse or contrition."

Kumuthini Kannan was sentenced to eight years in jail, the same amount of time she held a Tamil woman against her will in her Mount Waverley home.(AAP: James Ross)

Kumuthini Kannan appeared in court from prison where she rocked back and forth during the hearing.

She put her hands to her face as her husband, Kandasamy Kannan, was sentenced.

He sat with his arms crossed and did not react.

The couple's victim, who cannot be named, originally came to Australia to work for them, and was able to return to India both times.

But on her third visit in 2007, she was enslaved by the Kannans and forced to cook, clean and care for the couple's children for eight years. She was effectively paid about $3.39 per day.

Prosecutors now want the court to order the couple to repay the woman for years of servitude.

Victim was 'fading away', weighing 40 kilograms

Justice Champion said the woman allowed the couple to maintain their jobs and their lifestyle, including holidays overseas.

In 2015, the victim's family became increasingly concerned about her welfare and, when they were unable to contact her, Victoria Police conducted a welfare check.

But the officer who went to the Kannan's house was told by the couple that they had not seen her since 2007.

In reality, the woman had been admitted to hospital under a fake name after she collapsed and was found in a pool of her own urine.

"Mrs Kannan called triple-0 for assistance, but not before deciding to take your children to a school concert, leaving [the woman] on the bathroom floor," Justice Champion said.

"You told a litany of lies designed to mislead and distance yourself and your husband from the true circumstances of the person who had been admitted to hospital."

The woman had to be admitted to intensive care and later told authorities she was beaten with a frozen chicken and burned with boiling water.

"She was emaciated and weighed about 40 kilograms," Justice Champion said.

"She was described by a hospital doctor as fading away."

Couple considered slave a family member

The Supreme Court heard that the woman, who is now in her 60s, continues to suffer long-term health effects and will need a catheter for the rest of her life.

Kandasamy Kannan received a shorter sentence than his wife, who was found more morally culpable.(ABC News)

The court heard that she had declined to make a victim impact statement.

But lawyers for the Kannans argued that the woman's claims about being physically abused could not be conclusively proven.

During a pre-sentence hearing, their legal team told the court that they considered the woman a family member, and that she was never shackled.

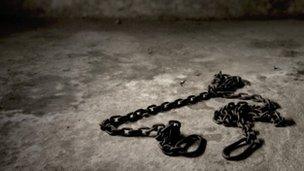

Justice Champion said the concept of slavery needed to be redefined.

"We must rid ourselves of ingrained images of rows of men chained together at the oars of a galley or men, women and children working in fields in bondage," he said.

"Slavery can be much more subtle than that, and may not involve physical restraint.

"It must be reaffirmed as that possessing or using a person in a condition of slavery is repugnant, degrading of the human condition, and a gross breach of human rights."

He said Kumuthini Kannan was more morally culpable for keeping the woman as a slave, compared to her husband who was more "at arm's length".

Kumuthini Kannan will be eligible for parole in four years.

Kandasamy Kannan can apply for parole in three years.

It is amazing even today people have been charged with Slavery in Australia!

Slavery and the Slave Trade | National Records of Scotland (nrscotland.gov.uk)Slavery and the Slave Trade

This guide deals primarily with aspects of the transatlantic slave trade and records in the National Records of Scotland (NRS). It also mentions some other Scottish archives relating to Scotland's involvement in the trade and its abolition. Some researchers are interested in information about enslaved individuals or former enslaved people, while others are interested in conditions or events on particular plantations, slave voyages, or the abolition movement. Research is also carried out in Scottish archives into other forms and aspects of slavery, for example the concepts of free and unfree status of women and serfs in medieval Scotland; transportation to the colonies of rebels during the religious wars and of criminals; bonded labour in the early modern period; and the enslavement of Scots by North African corsairs in the seventeenth century.

It is possible to carry out research on some of these subjects in the NRS, which holds the records of Scottish courts and churches, and some estate papers relating to plantations owned by enslavers. Other aspects of the trade are better researched elsewhere, for example in The National Archives, London, or in other archives and libraries. The following sections deal with aspects of the slave trade and suggest relevant sources of information.

Enslavement in Africa and slave trade voyagesThere is little evidence in the NRS of the enslavement and movement of the enslaved to African ports prior to shipping. Log books of ship voyages normally remain the property of ship owners and very few have found their way to Scottish archives. The NRS holds one letter describing a voyage on a slave trader from Bleney Harper (in Barbados) to William Gordon & Company, Glasgow, May 1731 (NRS reference CS228/A/3/19). A greater proportion of evidence on the enslavement and movement of enslaved persons can be found in The National Archives (in London) in the records of the African trading companies, Customs Outport, Board of Trade and the Admiralty. For more details see the research guides on the slave trade on The National Archives website (see below under United Kingdom government sources).

Where evidence of the slave trade voyages exists in Scotland it is generally through court cases. For example, four cases involving owners of ships engaged in the slave trade, which were heard in the High Court of Admiralty in Scotland are: Daniel v Graham, 1721 (NRS reference AC9/718), Clark v Inglis, 1727 (NRS reference AC9/1022), Horseburgh v Bogle, 1727 (NRS reference AC9/1042) and Alexander v Colhoun & Company, 1762 (NRS reference CS228/A/3/19). The records of the Horseburgh v Bogle case are important as they give very detailed information about the way in which the slave trade was carried out in the early eighteenth century. There are more than 70 items including financial records, witness statements and other legal papers providing evidence of the export of 'guinea goods' from Britain to Africa, the role of the ship's surgeon as supercargo in purchasing slaves for transportation, and his contract with the Scottish merchants who backed the venture.

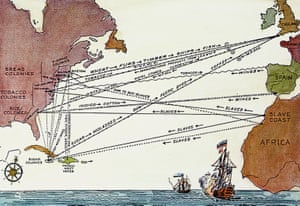

Enslavement markets and auctionsFollowing the union of parliaments in 1707, Scotland gained formal access to the transatlantic slave trade. Scottish merchants became increasingly involved in the trade and Scottish planters (especially sugar and tobacco) began to settle in the colonies, generating much of their wealth through enslaved labour. Evidence of the acquisition of enslaved individuals from slave traders and other enslavers can be found among the Estate and plantation records and the Business records of merchants and individuals involved in enslavement.

Enslaved individuals on plantationsThe main source of information in the NRS for events and conditions on plantations is estate papers of landowners in Scotland who owned plantations in the colonies. Letters, inventories and, occasionally, estate plans in these collections are an excellent source for researching the lives of enslaved persons on plantations in the colonies, their living conditions and the general attitude towards slavery and the slave trade. See below under estate and plantation records and also pictorial evidence.

Researching specific enslaved persons or former enslaved persons in ScotlandIt is usually time-consuming to find information about any individuals in Scotland who lived prior to mid-19th century, but there may be opportunities for researching enslaved or former enslaved individuals in Scotland. Church attendance for enslaved individuals was not allowed in most colonies on the grounds that baptism might have prompted enslaved individuals to claim their right to freedom as Christians. Once in Scotland, however, many enslaved people were allowed to be baptised, and evidence of this should be in old parish registers of baptisms. At the point of baptism enslaved or former enslaved individuals often took the surnames of their enslavers, which should be borne in mind when searching baptismal registers. Released enslaved people were also allowed to marry and you may find an entry for their marriage in the old parish registers of marriages.

In correspondence (social letters) and household records of families which enslaved people you might find letters or diaries referring to household enslaved individuals or accounts for things purchased for them. They sometimes also contain copies of wills, which might reveal if any enslaved people lived in the household and whether they were bequeathed themselves or were the recipients of the bequests. Lists of enslaved individuals are occasionally found in estate collections and these vary in the amount of detail they give, but they usually include the names of the enslaved person, their age, any other family members and sometimes origin and medical condition.

Some former enslaved individuals were employed as apprentices with tradesmen. To find out more about the different types of trade records, read our guide to crafts and trades.

In the late-eighteenth century there was a tax on some categories of servants in Scotland and surviving tax rolls for these are held by the NRS, arranged by burghs and counties and then by household, with the names of the servants and sometimes their jobs (NRS reference E326/5 and E326/6). For more details read our guide to taxation records.

After their release (or successful escape), some former enslaved people joined the Army. Muster rolls list new recruits and might mention any former enslaved persons that joined. Searching them can be an arduous and time-consuming task, so you should ideally know the regiment the individual served in and their complete name. For more information on muster rolls, see our guide on military records.

Until the abolition of slavery, the release of slaves was formalised through a 'manumission' (a legal document granting the slave his or her freedom). Manumissions are contained within the papers of the Colonial Office and Foreign Office, held at The National Archives (TNA) - see below under United Kingdom government sources.

Records of prominent former enslaved peopleNot much is known about how former enslaved persons integrated in Scottish society, how they felt about and utilised their freedom. This is because there are very few first-hand accounts in Scottish archives left by former enslaved people. However, some individuals were well-known in Scotland at their time, such as George Dale, who was transported against his will from Africa, aged about eleven and ended up in Scotland after an unusual career as a plantation cook and crewman on a fighting ship. In 1789, during the time of the French Revolution, The Society for the Purpose of Effecting the Abolition of the African Slave Trade gathered evidence like George Dale's life story for the anti-slavery abolitionist cause (NRS reference GD50/235). You can read a transcript of this document in the feature on George Dale on the Learning section of this website.

Another well-known former enslaved person was Scipio Kennedy. He had been brought to Scotland by Captain Andrew Douglas in 1702 from the West Indies, where he had been transported as a young boy from the African west coast. In 1705, Scipio joined the family of the Captain's daughter who married John Kennedy from Culzean in Ayrshire, and it was here that Scipio got his surname. He stayed in this family for an initial 20 years, during which time he was baptised and probably also received some education. Through his baptism, Scipio was free according to Scots law, so that when he decided after 20 years to continue service with his former owner for another 19 years, this was formalised by an indenture (NRS reference GD25/9/Box 72/9). Little is known about his later life, though he appears once in the kirk session minutes of Kirkoswald on 27 May 1728 (NRS reference CH2/562/1), accused of fornication with Margaret Gray, whom he later married. We know from references in the old parish registers that they had at least eight children and continued to live in Ayrshire until Scipio's death in 1774.

Between 1756 and 1778 three cases reached the Court of Session in Edinburgh whereby fugitives of slavery attempted to obtain their freedom. A central argument in each case was that the enslaved person, having been bought in the colonies, had been subsequently baptised by sympathetic church ministers in Scotland. The three cases were Montgomery v Sheddan (1756), Spens v Dalrymple (1769) and Knight v Wedderburn (1774-77). The last case was the only one decided by the Court. James Montgomery (formerly 'Shanker', the property of Robert Sheddan of Morrishill in Ayrshire) died in the Edinburgh Tolbooth before the case could be decided. David Spens (previously 'Black Tom', belonging to Dr David Dalrymple in Methill in Fife) sued Dalrymple for wrongful arrest but Dalrymple died during the suit. Joseph Knight sought the freedom to leave the employment of John Wedderburn of Bandean, who argued that Knight, even though he was not recognised as a enslaved individual, was still bound to provide perpetual service in the same manner as an indentured servant or an apprenticed artisan (see Court of Session cases below).

The abolition movementMany individual Scots were involved in the movement to abolish slavery or helped fugitives of slavery in Scotland in their quest for freedom. The Church of Scotland and other churches were also involved in the petitioning of parliament to abolish the slave trade in the late-eighteenth century and early-nineteenth century and individual church ministers baptised enslaved individuals in order to aid their attempts to gain freedom. The Court of Session cases challenging the status of slavery in Scotland reveal that local people helped fugitives of slavery – see under Court of Session cases. The NRS and SCAN online catalogues and the National Register of Archives can be used to some extent to search for material about the abolition movement and leading abolitionist figures, such as William Dickson of Moffat and William Wilberforce. See under 'Searching the NRS, SCAN and NRAS online catalogues' below. Researchers into the abolition movement in Scotland should refer to Iain Whyte, Scotland and the Abolition of Black Slavery, 1756-1838 (Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

Court of Session casesThe Court of Session, Scotland’s supreme civil court, heard some cases concerning the commercial and property-owning aspects of the slave trade. Three cases concerning the status of enslaved people in Scotland also survive among the unextracted processes of the court in the NRS, as follows:

Montgomery v Sheddan, 1756Among the petitions, declarations and other submissions by Sheddan and Montgomery in Court of Session (NRS reference CS234/S/3/12) there survives the bill of sale from Joseph Hawkins, Fredricksburg, to Robert Sheddan of ‘One Negroe boy named Jamie’ (9 March 1750). To read more, see the feature on the Montgomery slavery case on the Learning section of this website.

Spens v Dalrymple, 1769The papers in unextracted processes are NRS reference CS236/D/4/3 box 104 and NRS reference CS236/S/3/13. For more information, see the feature on the Spens slavery case in the Learning section of this website.

Knight v Wedderburn, 1774-7The unextracted processes for this case (NRS reference CS235/K/2/2) include an extract of process by the Sheriff Depute of Perth against Sir John Wedderburn (1774) and memorials by Wedderburn and Knight. For more information, see the feature on the Knight slavery case in the Learning section of this website.

Estate and plantation recordsScottish families who settled in the colonies maintained contact with their relatives in Scotland, and extensive series of correspondence survive in some Scottish estate collections. In these letters, the work and life of enslaved people on the plantations is often touched on, and we also learn how enslaved individuals rebelled against their captivity, either by absconding from their enslavers or through organised rebellion. Although most enslaved people were made to work on their enslaver’ plantations, enslaved individuals were often employed in their enslaver’ households as servants, and would occasionally be mentioned in letters or diaries. It was mostly these enslaved individuals whom enslavers would take with them if they returned to Scotland. Accounts reveal any expenditure made for enslaved persons, such as clothing, food and vaccines but also things like shackles and collars. Estate collections sometimes include household inventories drawn up at the death of the estate owner, which might mention enslaved people. Estate plans might show how enslaved individuals were accommodated. Some examples of plantation records in the NRS are Cameron and Company, Berbice, 1816-1824 (NRS reference CS96/972), William Fraser, Berbice, 1830-1831 (NRS reference CS96/1947), Robert Cunnyngham, St Christopher’s, 1729-1735, (NRS reference CS96/3102) and Earls of Airlie, Jamaica, 1812-1873, (NRS reference GD16/27/291). Our online catalogue can be searched by planter’s name, plantation name or by keywords such as ‘slavery’, ‘slaves’, 'negro', 'negroes', ‘plantation’ or a combination of keywords.

Business records of merchants and enslaversBusiness records (such as correspondence, accounts and ledgers) give an insight into how the slave trade was operated. Letters between slave traders can reveal how slave markets and auctions were identified and how slaves were transported to the colonies and sold there. Merchants’ correspondence relating to the slave trade often concerns the triangular trade with the colonies but may also include references to the abolition of the slave trade insofar as it affected their business. Letters to and from purchasers tell us about the characteristics customers typically looked for in enslaved individuals. Accounts will usually give the sum of money paid or received and may also mention the purchasers' names and the physical condition of the enslaved person. Although enslaved people's names are occasionally included as an ‘identifier’, normally only their first name is given. Examples of business records in the NRS, referring to the slave trade are Buchanan & Simpson, Glasgow, 1754-1773 (NRS reference CS96/502-509) and Cameron and Company, Berbice, 1816-1824 (NRS reference CS96/972-983). The CS96 records normally relate to Court of Session cases, whose references may be found in the same catalogue entry. To find relevant business records, you would ideally know the name of the company or individual dealing in eslavement, as the entries in our online catalogue are arranged by record creator. However, the above examples were identified by using relevant search terms such as ‘slave’, ‘slaves’ and ‘slave trade’.

Wills and testamentsThere is evidence from wills and testaments that enslaved people in the colonies were regarded as ‘moveable property’, meaning they could be bequeathed after the owner’s death. Copies of original testaments of plantation owners may survive in estate papers or among family papers. If the testament was registered by a court whose jurisdiction covered the plantation itself, the registers might survive in the relevant national archives of that country. Scots who owned land in both the colonies and in Scotland could have their testaments registered in the Commissary Court of Edinburgh and (later) the Sheriff Court of Edinburgh. The registers for both of these have been digitised and are searchable online via the ScotlandsPeople website. See below under 'websites and bibliography'.

Registers of DeedsContracts, indentures, factories and other legal papers concerning the sale of enslaved people can give details about the transaction, the parties involved, the price paid and other conditions under which the sale was to be finalised. Some of these are among collections of estate and plantation records or family papers (e.g. indenture between John Davies, Antigua, and James Matthew Hodges, Antigua, regarding the sale of a enslaved person, 1833 (NRS reference GD209/21) and indenture between Eliza Mines, Jamaica, and Cunningham Buchanan, Jamaica, regarding sale of two female enslaved individuals, 1809 (NRS reference CS228/B/15/52). It is possible that many others might appear in the various registers of deeds in the NRS, which can be very time-consuming to search. Many registers are not indexed, and those which are indexed are only by personal name. For more details see our research guide on searching registers of deeds.

Pictorial evidenceThe NRS frequently receives enquiries for images of enslavement, the slave trade, the abolition movement, aspects of plantation life and related topics. Almost all of the information in the NRS relating to these topics is in written form. The best source of pictorial illustrations and images in Scotland is Glasgow City Libraries and Archives. A good starting point is the 2002 exhibition ‘Slavery and Glasgow’, which is available online at the Scottish Archive Network (SCAN) website.

MapsTwo published maps of the Gold Coast have come to the NRS via private record collections: (1) map of Africa according to Mr. D'Anville with additions and improvements and a particular chart of the Gold Coast, showing European forts and factories, 1772, published by Robert Sayer, London (NRS reference RHP2069), and (2) map of Africa, improved and enlarged from D'Anville's map, including inset map of the Gold Coast and vignette of African figures, 1794, published by Laurie & Whittle, London (NRS reference RHP9779). Some access restrictions apply to the second map: consult NRS Historical Search Room staff.

Searching NRS, SCAN and NRAS online cataloguesThe NRS online catalogue contains many detailed entries at item level, and it is possible to search it using terms such as ‘slave’ and ‘slavery’, and by the name of a plantation or plantation owner. It is less likely to yield information on enslaved individuals and former enslaved individuals unless they became well-known.

The Scottish Archive Network (SCAN) online catalogue contains summary details of collections of records in more than 50 Scottish archives. Again this might be useful for searching for records of plantations and their owners, but not many other aspects of slavery. The SCAN website also contains the exhibition Slavery and Glasgow, which displays images of many of the types of material covered by this guide.

The online register of the National Register of Archives for Scotland (NRAS) is a catalogue of records held privately in Scotland.

United Kingdom government sourcesActs, statutes and slave registersThe Act of 1807 only abolished the transatlantic slave trade (the shipping of enslaved people from Africa to the colonies in the Americas). The sale and transport of enslaved people between colonies were not affected by this legislation. Moreover, in spite of the new law, the slave trade across the Atlantic continued illicitly. In response to this, the British government passed a Bill in 1815, requiring the registration of legally-purchased slaves in the colonies. The system of slave registration was gradually introduced by 1817. The registers are an excellent source for researching enslaved individuals. The amount of detail they give varies, but you can generally expect to find the enslaver’s name, the enslaved person’s name, age, country of birth, occupation and further remarks. You should be aware when studying these records that there was some opposition to the registration bill among enslavers, so the registers are not complete. The NRS does not hold slave registers. For most former colonies, you will need to contact the respective national archive services.

In 1816, another Act came into force, requiring an annual return of the enslaved population in each colony. The returns were obtained by parish and normally record the enslaver’s name and the number of male and female enslaved people in their possession; they do not normally include the enslaved person’s names. These records are a good source for identifying individual enslavers. Returns were taken until 1834.

During the 1820s, the British government began to make provisions for the gradual amelioration of slavery. This development towards its complete abolition in the British colonies is well documented in private and business letters from enslavers as well as speeches and pamphlets by abolitionists (see under 'the abolition movement' above). The new measures imposed by the government included Acts for the ‘government and protection of the slave population’, passed between 1826 and 1830. These Acts addressed topics such as minimum standards for food and clothing, labour conditions, penal measures and provisions for old and sick enslaved individuals. In Jamaica, enslaved persons could no longer be separated from their families, and released enslaved people were allowed to own personal property and to receive bequests. Murder of an enslaved person was to be punished with death. In Barbados, owners were instructed to have all their enslaved individuals baptised and clergymen were required to record births, baptisms, marriages and deaths occurring in the enslaved population. Enslaved people charged with capital offences were to be tried in court in the same way as white and free-coloured persons. In Grenada, every enslaved individual was to be given a proportion of land adequate to their support and be granted 28 working days per year to cultivate it. In Antigua, enslavers were required to build a two-roomed house for every enslaved female pregnant with her first child. A printed abstract of these Acts is held within a private collection (NRS reference GD142/57). For further information see the Parliamentary Archives website.

ManumissionsOccasionally, enslavers would decide to release some of their enslaved people. The release was formalised through a ‘manumission’ (a document granting the enslaved person his or her freedom). Manumissions are contained within the papers of the Colonial Office and Foreign Office, held at The National Archives (TNA). For more details of these and the records of the Office of the Registry of Colonial Slaves and Slave Compensation Commission, 1812-1851, including the central register of slaves in London, see the research guides on the slave trade on The National Archives website.

There are also some individual manumissions contained in estate papers held privately in Scotland. To search these and to find out more about how to access them, see National Register of Archives for Scotland online register.

Websites and bibliographyScottish Archive Network (SCAN) - use the online catalogue to search for records relating to slavery in Scottish archives and view the Slavery and Glasgow exhibition

BooksThe National Archives, London (TNA) - consult the research guides on slavery and the slave trade

One Scotland website - includes a list of resources on Scotland and the slave trade

Scottish Government National Improvement Hub - learning resources concerning slavery and human trafficking

ScotlandsPeople - census returns; civil registers of births, deaths and marriages (from 1855 onwards); Old Parish Registers of baptisms and marriages; wills and testaments registered in Scotland

Parliamentary Archives website - includes a micro-site: Parliament and the British Slave Trade

Eric J Graham, A Maritime History of Scotland 1650-1790 (Tuckwell Press, 2002)

Eric J Graham, Seawolves: Pirates and the Scots (Birlinn Ltd, 2007)

David Hancock, Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community, 1735-1785, (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Alan L Karras, Sojourners in the Sun: Scottish Migrants in Jamaica and the Chesapeake, 1740-1800 (Cornell University Press, 1992)

Kenneth Morgan, Slavery, Atlantic Trade and the British Economy, 1660-1800 (Cambridge University Press, 2001)

Iain Whyte, Scotland and the Abolition of Black Slavery, 1756-1838 (Edinburgh University Press, 2006)

Frances Wilkins, Dumfries and Galloway and the Transatlantic Slave Trade (Wyre Forest Press, 2007)